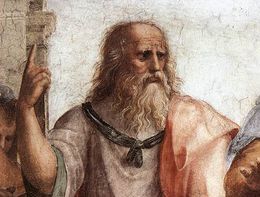

Plato (427 - 347 BC)

(427 - 347 BC)

Background

The Socratic Method - Dialectical Reasoning

The Socratic Method - Dialectical Reasoning

Plato addresses three basic complaints in The Republic

The Format of Plato’s Discussion

The Format of Plato’s Discussion

Plato introduces the Subject of the Republic

Plato’s View of Doing Right: the just man lives the best life

Plato’s View of Doing Right: the just man lives the best life

Types of Society and Character

Types of Society and Character

Society and the Common Good

Society and the Common Good

Plato as an Enlightened Intellect

Background

Plato was born in the city state of Athens in the fourth year of its epic war with Sparta. Pericles had succumbed in the previous year to a plague that ravaged the warring city. Plato lived through his childhood, youth, and young-manhood in an atmosphere defined by danger, suffering and uncertainty. In his 23rd year, Athens met its final defeat. The culmination of the military conflict marked the beginning of an upheaval within Athenian society, which brought the end of the “Golden Age of Pericles” and the democractic government he had championed. A commission of thirty citizens (which included Plato’s uncle Critias) was created to draft a new constitution. In the aftermath of a generation of war, there was less concern to frame an new government than to settle old scores. Instead of defining the common good and enacting laws to accomplish it, The Thirty used their power to persecute their political opponents. Seven months of this tyranny brought the citizens of Athens into rebellion. The tyrants were driven from power and a new democratic constitution was instituted. Plato described these events in his Seventh Letter which he wrote in his later years. There he wrote:

Plato was born in the city state of Athens in the fourth year of its epic war with Sparta. Pericles had succumbed in the previous year to a plague that ravaged the warring city. Plato lived through his childhood, youth, and young-manhood in an atmosphere defined by danger, suffering and uncertainty. In his 23rd year, Athens met its final defeat. The culmination of the military conflict marked the beginning of an upheaval within Athenian society, which brought the end of the “Golden Age of Pericles” and the democractic government he had championed. A commission of thirty citizens (which included Plato’s uncle Critias) was created to draft a new constitution. In the aftermath of a generation of war, there was less concern to frame an new government than to settle old scores. Instead of defining the common good and enacting laws to accomplish it, The Thirty used their power to persecute their political opponents. Seven months of this tyranny brought the citizens of Athens into rebellion. The tyrants were driven from power and a new democratic constitution was instituted. Plato described these events in his Seventh Letter which he wrote in his later years. There he wrote:

“Not long after the Thirty fell, the constitution was changed. And again though less keenly, I felt the desire to enter politics. Those were tremulous times, and many things were done to which one could object, nor was it surprising that vengeance should sometimes be excessive in a revolution. None the less the returned democrats behaved on the whole, with moderation. Unfortunately, however, some of those in power brought my friend Socrates to trial on a monstrous charge, the last that could be made against him, the charge of impiety; and he was condemned and executed.”

Plato’s faith in democracy as a form of government was shattered by this act. It inspired him to write The Republic. Continuing from the Seventh Letter, Plato wrote

Plato’s faith in democracy as a form of government was shattered by this act. It inspired him to write The Republic. Continuing from the Seventh Letter, Plato wrote

“Finally I came to the conclusion that all existing states were badly governed, and that their constitutions were incapable of reform without dramatic treatment and a great deal of luck. I was forced, in fact, to the belief that the only hope of finding justice for society or for the individual lay in true philosophy, and that mankind will have no respite from trouble until either real philosophers gain power, or politicians become by some miracle true

philosophers.”

Plato presented human nature as a powerful natural force, which could be shaped–and managed. Following this view, he introduced the thesis that society could be made perfect through the institution of what amounted to better government. Plato developed this thesis in a far-reaching discussion on the manufacture of the philosopher- kings who he intended to be the leaders of his government. Plato sought to form the character of his novitiates on this standard of perfection. Governed themselves by this perfection, Plato’s philosopher-kings would have the ability to transform society into utopia. Desmond Lee notes in his introduction to The Republic that Plato “dealt at length with education, with the moral principles underlying the organization of society, as well as the general lines on which it should be organized. We therefore have a book which is as much about ethics and education and philosophy as about politics in the strict sense.” [Lee, p. 32.]

Plato presented human nature as a powerful natural force, which could be shaped–and managed. Following this view, he introduced the thesis that society could be made perfect through the institution of what amounted to better government. Plato developed this thesis in a far-reaching discussion on the manufacture of the philosopher- kings who he intended to be the leaders of his government. Plato sought to form the character of his novitiates on this standard of perfection. Governed themselves by this perfection, Plato’s philosopher-kings would have the ability to transform society into utopia. Desmond Lee notes in his introduction to The Republic that Plato “dealt at length with education, with the moral principles underlying the organization of society, as well as the general lines on which it should be organized. We therefore have a book which is as much about ethics and education and philosophy as about politics in the strict sense.” [Lee, p. 32.]

The Republic

Plato’s concern in The Republic was to solve the problem of social decay in which disunity and violence undermine society and destroy the possibility of living the good life

Plato’s concern in The Republic was to solve the problem of social decay in which disunity and violence undermine society and destroy the possibility of living the good life

The Socratic Method - Dialectical Reasoning

Plato’s method of reasoning is sometimes called the "Socratic Method". In this mode of reasoning, an interviewer (Socrates) analyses a philosophical

Plato’s method of reasoning is sometimes called the "Socratic Method". In this mode of reasoning, an interviewer (Socrates) analyses a philosophical

concept (in The Republic Plato analyzes the concept of Justice or “doing right”) by asking his companions questions and pointing out the errors in their answers. As this method of reasoning occurs in conversations (dialogues) between members of a group, it is also called dialectic reasoning, or simply dialectic.

Socrates arrived at the truth by revealing the errors in his companions’ definitions. Only one thing can be right for Socrates (and Plato). Everything that disagrees with what is right must therefore be wrong. This proposition reflects Plato’s underlying view about the nature of the world (i.e., his metaphysics). In Plato’s metaphysics, there are ultimate, universal, unchanging truths. These truths define a comprehensive and eternal order. These truths and this order constitute the real world.

Socrates arrived at the truth by revealing the errors in his companions’ definitions. Only one thing can be right for Socrates (and Plato). Everything that disagrees with what is right must therefore be wrong. This proposition reflects Plato’s underlying view about the nature of the world (i.e., his metaphysics). In Plato’s metaphysics, there are ultimate, universal, unchanging truths. These truths define a comprehensive and eternal order. These truths and this order constitute the real world.

The Similie of the Cave [Lee pp. 316-325]

• Platonic truths inhere in an unchanging world that exists, so to speak,

Platonic truths inhere in an unchanging world that exists, so to speak,

beyond the realm of the senses

• These truths are for Plato the perfect forms or essences of things that

These truths are for Plato the perfect forms or essences of things that

exist in the world of sense. Essences are universal and eternal

• The form or essence of a thing is for Plato the excellence that allows it to perform it proper function well

The form or essence of a thing is for Plato the excellence that allows it to perform it proper function well

Plato addresses three basic complaints in the Republic:

1)  people are bad judges both in respect to their own self interest and in respect to matters that pertain to the good of their society and state [Lee, 27.]

people are bad judges both in respect to their own self interest and in respect to matters that pertain to the good of their society and state [Lee, 27.]

2) democracy encourages bad leadership [Lee, 28.]

democracy encourages bad leadership [Lee, 28.]

3) Where individuals are free to do as they please, as they are in

Where individuals are free to do as they please, as they are in

democracies, there is a growing dislike for political and moral

authority

The Format of Plato’s Discussion:

Part I.

Part I.  Introduction

Introduction

•

• The question of what it is to do right (being just)

The question of what it is to do right (being just)

•

• Doing right is giving every man his due

Doing right is giving every man his due

•

• Justice or right what is interest of the stronger

Justice or right what is interest of the stronger

Part II.  Preliminary Discussions

Preliminary Discussions

•

• Socrates says it is easier to discuss things on a large scale and

Socrates says it is easier to discuss things on a large scale and

proposes to discuss justice in the state and community first

proposes to discuss justice in the state and community first

•

• Society forms in a process of natural growth - like a man in health

Society forms in a process of natural growth - like a man in health

•

• The state needs to be defends, he Plato creates a “Guardian Class”

The state needs to be defends, he Plato creates a “Guardian Class”

and turns his attention to the qualities of character guardians must

and turns his attention to the qualities of character guardians must

have to preserve the state

have to preserve the state

•

• excellence allows a thing to perform its function well

excellence allows a thing to perform its function well

•

• Justice is the excellence of the mind, injustice is its defect

Justice is the excellence of the mind, injustice is its defect

Part III Education - the First Stage

Education - the First Stage

•

• Education would be the responsibility of the state

Education would be the responsibility of the state

•

• It would focus on reading, writing, physical training, and “literary

It would focus on reading, writing, physical training, and “literary

education” (learning wisdom by studying the poets)

education” (learning wisdom by studying the poets)

•

• Children are to be moved from class to class according to their

Children are to be moved from class to class according to their

abilities

abilities

•

• Men and women are to have the same education and training

Men and women are to have the same education and training

Part IV.  Guardians and Auxiliaries

Guardians and Auxiliaries

•

• Two class of Guardians

Two class of Guardians

•

• Rulers

Rulers

•

• Auxiliaries

Auxiliaries

•

• The “Foundation Myth” expresses/embodies the values that the

The “Foundation Myth” expresses/embodies the values that the

community wishes to actualize [Lee, 181]

community wishes to actualize [Lee, 181]

Part V.  Justice in the State and in Individuals

Justice in the State and in Individuals

•

• The ideal state must have four qualities or virtues: wisdom, courage,

The ideal state must have four qualities or virtues: wisdom, courage,

discipline and justice

discipline and justice

•

• Justice according to Plato is to do the job for one which one is

Justice according to Plato is to do the job for one which one is

naturally fitted and to mind one’s own business

naturally fitted and to mind one’s own business

•

• The three elements of the soul must be in harmony for the

The three elements of the soul must be in harmony for the

individual to achieve a good life, which for Plato is to be just.

individual to achieve a good life, which for Plato is to be just.

•

• Justice in the individual is defined [Lee, p. 221]

Justice in the individual is defined [Lee, p. 221]

Part VI.  Women and the Family

Women and the Family

•

• Plato digresses with a discussion of the place of women and the

Plato digresses with a discussion of the place of women and the

family in society

family in society

•

•  the only difference between men and women is that one begets and

the only difference between men and women is that one begets and

the other bears children

the other bears children

Part VII. The Philosopher Ruler

Part VII. The Philosopher Ruler

•

• the only hope for realizing the ideal state is that political power is

the only hope for realizing the ideal state is that political power is

placed in the hands of philosophers

placed in the hands of philosophers

•

• the philosopher loves wisdom, learning, knowledge and truth

the philosopher loves wisdom, learning, knowledge and truth

•

• because philosophers have these qualities of character, they are

because philosophers have these qualities of character, they are

able to understand the good–true happiness

able to understand the good–true happiness

Part VIII. Education of the Philosopher

Part VIII. Education of the Philosopher

•

• Philosopher rulers receive additional training in mathematics, and in

Philosopher rulers receive additional training in mathematics, and in

pure philosophy (Dialectic) which Plato conceives to be a rational

pure philosophy (Dialectic) which Plato conceives to be a rational

form of argument that allows its practitioners to realize the external

form of argument that allows its practitioners to realize the external

truth - things as they really are

truth - things as they really are

Part IX.

Part IX.  Imperfect Societies

Imperfect Societies

•

• decay causes the perfect society to dissolve into societies with

decay causes the perfect society to dissolve into societies with

different forms

different forms

•

• the decayed societies produce individuals with correspondingly

the decayed societies produce individuals with correspondingly

decayed characters

decayed characters

•

• The worst character–that of the tyrant–is totally corrupt and has no

The worst character–that of the tyrant–is totally corrupt and has no

justice and therefore no possibility of living well or being happy

justice and therefore no possibility of living well or being happy

Part X.

Part X.  Theory of Art

Theory of Art

•

• An appendix written perhaps to defend against criticism leveled

An appendix written perhaps to defend against criticism leveled

leveled against the poets

leveled against the poets

Part XI.

Part XI.  The Immortality of the Soul and the Rewards of Goodness

The Immortality of the Soul and the Rewards of Goodness

•

• The soul is immortal because its own evil cannot destroy it

The soul is immortal because its own evil cannot destroy it

•

• Goodness is its own reward

Goodness is its own reward

Plato introduces the Subject of the Republic:

Plato encounters Cephalus who is an authority on the subject of life by virtue of his age:

Plato encounters Cephalus who is an authority on the subject of life by virtue of his age:

“I enjoy talking to very old men, for they have gone before us, as it were, on a road that we too may have to tread, and it seems to me that we should find out from them what it is like and whether it is rough and difficult or broad and easy. You are now at an age when you are, as the poets say, about to cross the threshold, and I would like to find out how it strikes you and what you have to tell us.” [Lee, p. 62-63.]

“I enjoy talking to very old men, for they have gone before us, as it were, on a road that we too may have to tread, and it seems to me that we should find out from them what it is like and whether it is rough and difficult or broad and easy. You are now at an age when you are, as the poets say, about to cross the threshold, and I would like to find out how it strikes you and what you have to tell us.” [Lee, p. 62-63.]

Cephalus frames the discussion of The Republic by noting that as death approaches–and the fear of judgment in the next world–men think about the wrong they have done in this one. Plato goes on in the course of his text to explain that:

Cephalus frames the discussion of The Republic by noting that as death approaches–and the fear of judgment in the next world–men think about the wrong they have done in this one. Plato goes on in the course of his text to explain that:

•

• To do right is to be just

To do right is to be just

•

• Justice is the excellence or virtue of the soul

Justice is the excellence or virtue of the soul

•

• The just man will live well

The just man will live well

•

• He who lives well is blessed and happy

He who lives well is blessed and happy

Plato’s View of Doing Right: the just man lives the best life:

The real concern with justice “is not with external actions, but with a man’s inward self, his true concern and interest.” [Lee, p. 221.]

The real concern with justice “is not with external actions, but with a man’s inward self, his true concern and interest.” [Lee, p. 221.]

“I call anything that harms or destroys a thing evil, and anything that preserves and benefits it good.” [Lee, p. 441]

What is right and what is wrong are the elements of the concept of Justice. Like everything else in the real, eternal world, Plato (Socrates) considers them to be fixed. In Plato’s view, one does right because reason confirms that is conduces to the good life, which is defined in terms of personal happiness. For this reason, justice is a condition for a good society. (Justice in the individual is further discussed in Part IV [Collected Works, pp 684-689.])

What is right and what is wrong are the elements of the concept of Justice. Like everything else in the real, eternal world, Plato (Socrates) considers them to be fixed. In Plato’s view, one does right because reason confirms that is conduces to the good life, which is defined in terms of personal happiness. For this reason, justice is a condition for a good society. (Justice in the individual is further discussed in Part IV [Collected Works, pp 684-689.])

According to Plato, there are three elements of the soul:

According to Plato, there are three elements of the soul:

1)

1)  Reason - the faculty that calculates and decides

Reason - the faculty that calculates and decides

2)

2)  appetite (or desire) - in the sense of physical craving

appetite (or desire) - in the sense of physical craving

3)

3)  the character that gives rise to unthinking impulses (e.g.,

the character that gives rise to unthinking impulses (e.g.,

ambition, pugnacity, anger, etc...

ambition, pugnacity, anger, etc...

The rational part of the soul, having been educated to do its work, presides “over the appetitive part which is the mass of the soul in each of us and the most insatiate by nature of wealth.” [CW, p. 684.]

The rational part of the soul, having been educated to do its work, presides “over the appetitive part which is the mass of the soul in each of us and the most insatiate by nature of wealth.” [CW, p. 684.]

“But the truth of the matter was, as it seems, that justice is indeed something of this kind, yet not in regard to the doing of one’s own business externally, but with regard to that which is within and in the true sense concerns one’s self, and the things of one’s self. It means that a man must not suffer the principles in his soul to do each the work of some other and interfere and meddle with one another, but that he should dispose well of what in the true sense of the word is properly his own, and having first attained to self-mastery and beautiful order within himself, and having harmonized these three principles, the notes or intervals of three terms quite literally the lowest, the highest, and the

mean, and all others there may be between them, and having linked and bound all three together and made of himself a unit, one man instead of many, self-controlled and in unison, he should then and then only turn to practice if he find aught to do either in the getting of wealth or the tendency of the body or it may be in political action or private business...”

[CW, p. 686.]

Virtue then, as it seems, would be a kind of health and beauty and good condition of the soul, and vice would be disease, ugliness, and weakness. [CW, p. 687.]

Virtue then, as it seems, would be a kind of health and beauty and good condition of the soul, and vice would be disease, ugliness, and weakness. [CW, p. 687.]

Having set things in this order, Plato turns back to the issue Thrasymachus raised, “whether is profitable to do justice and practice honourable pursuits and be just, whether one is known to be such or not,

Having set things in this order, Plato turns back to the issue Thrasymachus raised, “whether is profitable to do justice and practice honourable pursuits and be just, whether one is known to be such or not,

or whether injustice profits, and to be unjust, if only a man escape punishment and is not bettered by chastisement. [CW, p. 687.]

Types of Society and Character:

Besides the ideal society, which is a community of men with this character, Plato recognizes four others:

Besides the ideal society, which is a community of men with this character, Plato recognizes four others:

1) Timarchy

1) Timarchy  an “ambitious society”/ a military aristocracy

an “ambitious society”/ a military aristocracy

2) Oligarchy

2) Oligarchy  where wealth is the criterion for merit and control

where wealth is the criterion for merit and control

3) Democracy where there is political opportunity and freedom

3) Democracy where there is political opportunity and freedom

for the individual to do as he likes [Lee, 373-381]

for the individual to do as he likes [Lee, 373-381]

4) Tyranny

4) Tyranny where a popular champion controls the government

where a popular champion controls the government

Plato argues that these societies emerge one after the other as the ideal society decays. The rule of the wise, gives way to Timocracy, which is the rule of nobles seeking honor and fame. Then comes Oligarchy, which is the rule of rich families. This is followed by Democracy, which Plato equates to lawlessness. Finally there is the rule of tyrants, which is Tyranny.

Plato argues that these societies emerge one after the other as the ideal society decays. The rule of the wise, gives way to Timocracy, which is the rule of nobles seeking honor and fame. Then comes Oligarchy, which is the rule of rich families. This is followed by Democracy, which Plato equates to lawlessness. Finally there is the rule of tyrants, which is Tyranny.

Society begins to degenerate, says Plato, when sophocrats start to show off and spend money. This causes rivalries and efforts to twist the law to create personal advantages. The result is class conflict. At first it is between the established feudal order and the new order of wealth–a conflict between virtue and money if you will. The transition to oligarchy is completed when the rich establish laws that disqualify those whose means do not reach a stipulated amount from holding public office. Establishment of the oligarchy sets the stage for civil war with the poorer classes aligned against the rich. War begins when one party or the other becomes stronger.

Society begins to degenerate, says Plato, when sophocrats start to show off and spend money. This causes rivalries and efforts to twist the law to create personal advantages. The result is class conflict. At first it is between the established feudal order and the new order of wealth–a conflict between virtue and money if you will. The transition to oligarchy is completed when the rich establish laws that disqualify those whose means do not reach a stipulated amount from holding public office. Establishment of the oligarchy sets the stage for civil war with the poorer classes aligned against the rich. War begins when one party or the other becomes stronger.

Democracy is born when the poor win the day. They celebrate their victory by killing off some of their vanquished foes. They banish a few others. But with the rest they share the rights of citizenship and public office on equal terms.

Democracy is born when the poor win the day. They celebrate their victory by killing off some of their vanquished foes. They banish a few others. But with the rest they share the rights of citizenship and public office on equal terms.

Society and the Common Good:

Plato mentioned the "social contract" in the Republic. He seems, however, to have preferred the idea that society formed in an organic process. Desmond Lee characterized this process as one of “natural growth”. Plato presents it in this exchange between Socrates and Adeimantus:

Plato mentioned the "social contract" in the Republic. He seems, however, to have preferred the idea that society formed in an organic process. Desmond Lee characterized this process as one of “natural growth”. Plato presents it in this exchange between Socrates and Adeimantus:

“Well then,” said I [Socrates], “if we were to look at a community coming into existence, we might be able to see how justice and injustice originate in it.”

“We might.”

“Do you think, then, that we should attempt such a survey? For it is, I assure you, too big a task to undertake without thought.”

“We know what we are in for,” returned Adeimantus; “go on.”

“Society originates, then,” said I, “so far as I can see, because the individual is not self-sufficient, but has many needs which he can’t supply himself. Or can you suggest any other origin for it?”

“No, I can’t,” he said.

And when we have got hold of enough people to satisfy our many needs, we have assembled quite a large number of partners and helpers together to live in one place; and we give the resultant settlement the name of community?”

“Yes, I agree.”

“And in the community all mutual exchanges are made on the assumption that the parties to them stand to gain?”

“Certainly.”

“Come then,” I said, “let us make an imaginary sketch of the origin of the

state. It originates, as we have seen, from our needs.”

Plato describes the good this society serves in the following exchange:

“Then, Adeimantus, can we now say that our state is full?”

“Yes, I think so.”

“If so, where are we to find justice and injustice in it? With the introduction of which of the elements we have examined do they originate?”

“I don’t know, Socrates,” he replied, “unless they arise somewhere in the mutual relationship of these elements."

“You may be right,” said I; “we must press on with our inquiry. So let us first consider how our citizens, so equipped will live. They will produce corn, wine, clothes, and shoes, and will build themselves houses. In the summer they will for the most part work unclothed and unshod, in the winter they will be clothed and shod suitably. For food they will prepare wheat-meal or barley meal for baking or kneading. They will serve splendid cakes and loaves on rushes or fresh leaves, and will sit down to feast with their children on couches or myrtle and bryony; and they will have wine to drink too, and pray to the gods with garlands on their heads, and enjoy each other’s company And fear of poverty and war will make them keep the numbers if their

families within their means.”

“I say,” interrupted Glaucon, “that’s pretty plain fare for a feast isn’t it?”

“You’re quite right,” said I. “I had forgotten; they will have a few luxuries. Salt, of course, and olive oil and cheese, and different kinds of vegetables from which to make various country dishes. And we must give them some dessert, figs and peas and beans, and myrtle-berries and acorns to roast at the fire as they sip their wine. So they will lead a peaceful and healthy life, and probably die at a ripe old age, bequesting a similar way of life to their children."

This society, Plato goes on to say, “seems to me to be the true one, like a man in health.” It was a simple society that conduced to peace and prosperity. This was not a society Plato knew from personal experience. He had grown to manhood during Athens’ twenty-seven year war with Sparta and witnessed the ensuing upheaval which culminated in tyranny and the execution of his friend and mentor, Socrates. Disillusioned by these events, Plato concluded that democracy did not conduce to the common good–or to justice. In keeping with Socrates’ effort to define the meaning of justice and right behavior, Plato eventually set about manufacturing the “true” state.

This society, Plato goes on to say, “seems to me to be the true one, like a man in health.” It was a simple society that conduced to peace and prosperity. This was not a society Plato knew from personal experience. He had grown to manhood during Athens’ twenty-seven year war with Sparta and witnessed the ensuing upheaval which culminated in tyranny and the execution of his friend and mentor, Socrates. Disillusioned by these events, Plato concluded that democracy did not conduce to the common good–or to justice. In keeping with Socrates’ effort to define the meaning of justice and right behavior, Plato eventually set about manufacturing the “true” state.

In his introduction to his translation of The Republic, Lee states that “we may briefly sum up by saying that disunity, incompetence and violence, which he had seen at Athens and at Syracuse, were the main dangers against which Plato thought society must be protected.” Plato meant to accomplish this by establishing a state ruled by “philosophers”.

In his introduction to his translation of The Republic, Lee states that “we may briefly sum up by saying that disunity, incompetence and violence, which he had seen at Athens and at Syracuse, were the main dangers against which Plato thought society must be protected.” Plato meant to accomplish this by establishing a state ruled by “philosophers”.

The healthy society Plato described early in The Republic seems “natural” enough, but the machinery he designed to sustain it was entirely synthetic. The philosopher kings who were to govern Plato’s republic learned their profession through rigorous training. Those who mastered the “royal art” joined an overclass that maintained the social order against internal disruptions and external aggression. It was a sophacracy–a system in which the wise rule. At the same time, it was a civil society which had neither factions nor mechanisms by which “the people” could express their will. Thomas Jefferson would have considered it a tyranny. Plato saw the picture differently.

The healthy society Plato described early in The Republic seems “natural” enough, but the machinery he designed to sustain it was entirely synthetic. The philosopher kings who were to govern Plato’s republic learned their profession through rigorous training. Those who mastered the “royal art” joined an overclass that maintained the social order against internal disruptions and external aggression. It was a sophacracy–a system in which the wise rule. At the same time, it was a civil society which had neither factions nor mechanisms by which “the people” could express their will. Thomas Jefferson would have considered it a tyranny. Plato saw the picture differently.

The calamities of the Peloponnesian War had proven government by “the people” to be unsound. Equally bad was the character of the person democracy produced. “When a young man,” Plato warned, “brought up in the narrow economical way we have described, gets a taste of the drones honey and gets into brutal and dangerous company, where he can be provided with every variety of refinement of pleasure, with the result that his internal oligarchy starts turning into a democracy.” “...he lives from day to day, indulging the pleasure of the moment. One day it’s wine, women and song, the next water to drink and a strict diet; one day it’s hard physical training, the next indolence and careless ease... Often he takes to politics and keeps jumping to his feet and saying or doing whatever comes into his head...There’s no order or restraint in his life and he reckons his way of living is pleasant, free and happy, and sticks to it through thick and

The calamities of the Peloponnesian War had proven government by “the people” to be unsound. Equally bad was the character of the person democracy produced. “When a young man,” Plato warned, “brought up in the narrow economical way we have described, gets a taste of the drones honey and gets into brutal and dangerous company, where he can be provided with every variety of refinement of pleasure, with the result that his internal oligarchy starts turning into a democracy.” “...he lives from day to day, indulging the pleasure of the moment. One day it’s wine, women and song, the next water to drink and a strict diet; one day it’s hard physical training, the next indolence and careless ease... Often he takes to politics and keeps jumping to his feet and saying or doing whatever comes into his head...There’s no order or restraint in his life and he reckons his way of living is pleasant, free and happy, and sticks to it through thick and

thin.” Defining the objectives of society and making its laws required more responsible and more qualified men.

Plato’s objective was to create rulers who would maintain society in relation to his vision of the good. He had relatively less interest in the individuals who populated his state and made no allowance for the possibility that it could be improved by their efforts to better themselves. The only concession he made to the Jeffersonian idea that individuals have a natural right to pursue happiness was the intimation that members of his ideal state would

be happy forever performing their hum-drum tasks and living out their healthy lives. Society’s greater responsibility was to preserve the communal good against the destructive forces of private interest and faction. To this end he endowed his ruling class guardians with the authority to suppress activities–and thoughts–deemed destructive to the master plan.

This invasive oversight and top-down management distinguished Plato’s concoction from the “natural growth” system Lee complimented. The form of his society was dictated by the good his system was intended to serve, not by the private interests of its members. Indeed, Plato considered ordinary people to be too flawed to be members of his rational system. They were, in Plato’s mind, self-interested, self-indulgent and incapable of distinguishing the immediate pleasure from the ultimate good. Achieving perfection in the Platonic state required not just a better class of rulers, but a better quality of citizens. His program for producing these new men can be construed as the opening assault in an ongoing war of Reason against Nature. In initiating this war, Plato created what would become the paradigm for Post-enlightened social activists.

This invasive oversight and top-down management distinguished Plato’s concoction from the “natural growth” system Lee complimented. The form of his society was dictated by the good his system was intended to serve, not by the private interests of its members. Indeed, Plato considered ordinary people to be too flawed to be members of his rational system. They were, in Plato’s mind, self-interested, self-indulgent and incapable of distinguishing the immediate pleasure from the ultimate good. Achieving perfection in the Platonic state required not just a better class of rulers, but a better quality of citizens. His program for producing these new men can be construed as the opening assault in an ongoing war of Reason against Nature. In initiating this war, Plato created what would become the paradigm for Post-enlightened social activists.

Plato as an Enlightened Intellect:

While Thomas Jefferson conceived of Democracy as the supreme political achievement--the ultimate fulfillment of the Enlightenment, Plato condemned democrats as profligate and niggardly, insolent, lawless and shameless, beasts of prey seeking to gratify every whim, living solely for pleasure, and for unnecessary and unclean desires.

While Thomas Jefferson conceived of Democracy as the supreme political achievement--the ultimate fulfillment of the Enlightenment, Plato condemned democrats as profligate and niggardly, insolent, lawless and shameless, beasts of prey seeking to gratify every whim, living solely for pleasure, and for unnecessary and unclean desires.

Plato is quite unenlightened in terms of Jefferson's frame of reference. Being an advocate, if not a strict practitioner of Newton's scientific methods, Jefferson was bound to reject Platonism and its Socratic method. But he was sensitive to one of Plato's key tenets--Plato said that the transition from democracy to tyranny begins when politicians begin to exploit class antagonisms to solidify their power.

Plato is quite unenlightened in terms of Jefferson's frame of reference. Being an advocate, if not a strict practitioner of Newton's scientific methods, Jefferson was bound to reject Platonism and its Socratic method. But he was sensitive to one of Plato's key tenets--Plato said that the transition from democracy to tyranny begins when politicians begin to exploit class antagonisms to solidify their power.