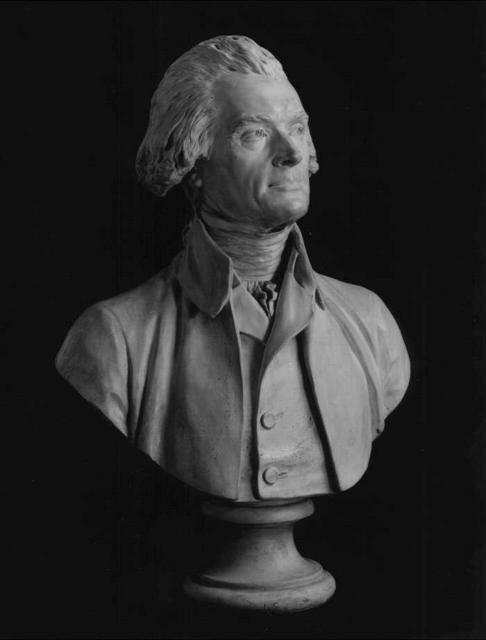

Bust of Thomas Jefferson

by

Jean-Antoine Houdon (1789)

Museum of Fine Arts Boston

(Library of Congress Image)

Introduction

Thomas Jefferson’s Enlightenment provides an interpretive account of an important

but inadequately explained transition in Jefferson’s political personality.

Jefferson began his career in the American patriotic movement as a reclusive political solipsist who prepared instructions for Virginia’s delegation to the 1st Continental Congress (1774), a plan for the new government of Virginia (1776), the Declaration of Independence (1776), and the sixty-six bills as a revisor of Virginia’s colonial code (1777-1779) alone and without consultation. In crisis moments before and during the America Revolution he withdrew from his public posts to the sanctuary of his mountaintop home. He had to be bullied into serving in the first Virginia assembly and standing for election as Virginia’s second governor. How did a man with a deep seeded and pervasive aversion to the confrontations entailed in political leadership become the head of a political faction, the leader of the “second American Revolution,” and the President of the United States of America? I believe the answer lies in Thomas Jefferson’s enlightenment, which I explain occurred in the second half of 1785 while he was serving his country as an ambassador in France.

Thomas Jefferson was famous before he went to France. In addition to his many notable accomplishments, he was brilliant. These and other credentials have earned him numberless accolades over the years, including Dumas Malone’s tribute to him as a “Disciple of the Enlightenment”. To be “enlightened” in the late-18th Century was to embrace the concept of Progress. Thomas Jefferson’s Enlightenment recounts how during his five year sojourn in France, Jefferson came to understand the enlightened concept of Progress. It goes on to explain that as he digested the dynamic worldview entailed in this enlightened concept, he underwent a personal transformation in which he complete his development as a political man capable of leadership.

This new political person, bolstered by his conviction that he had a part to play the perfection of man in society, revealed itself in his participation in Lafayette’s eleventh-hour effort to save France from civil war and again in his enthusiastic support for the revolution. Enlightenment also, I believe, stiffened his will to undertake a great new political initiative after he returned home.